College Numbers Down, Degrees Up: Understanding the Post-2010 Enrollment Shift

By Joe Winkelman, Gad Levanon and Mels de Zeeuw

After decades of expansion, American higher education has entered a period of contraction and reconfiguration. From the mid-1960s to 2010, college enrollment nearly quadrupled, reaching a peak of 21 million students. Since then, total enrollment has fallen by two million.

At first glance, this decline seems alarming. But a closer look reveals a more nuanced—and in some ways, encouraging—story.

Most of the decline is concentrated in undergraduate enrollment, particularly at community colleges. Four-year college enrollment has been more stable, and most of its losses came from the collapse of for-profit institutions. Demographics also played a role: as the 18–22 population shrank between 2012 and 2020, overall enrollment fell more dramatically than enrollment rates.

The good news: Enrollment rates at four-year colleges held firm. And thanks to rising completion rates, the share of young adults earning bachelor’s degrees continued to grow.

The surprising good news: Despite a steep drop in community college enrollment, associate degree attainment has not declined—because completion rates have improved dramatically.

In the pages that follow, we examine how and why these patterns emerged, with particular focus on the evolving role of community colleges. We also explore what these trends mean for the future.

A long era of enrollment growth came to an end in 2010.

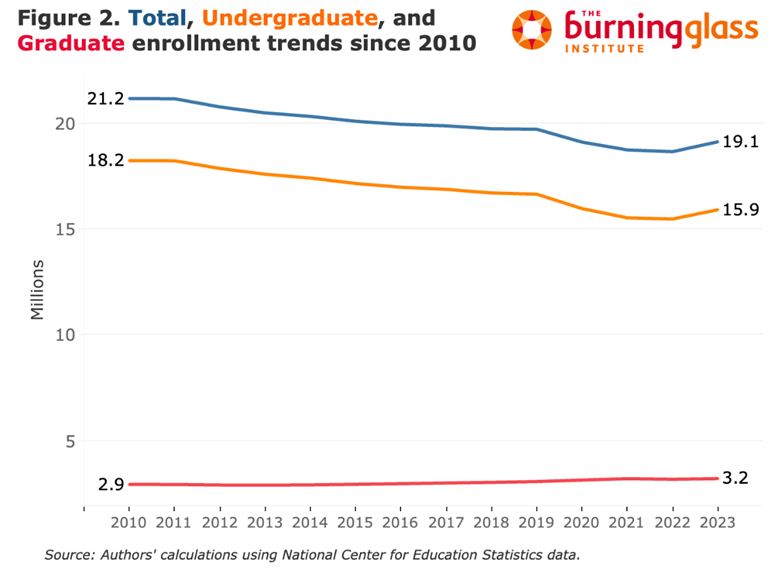

From the mid-1960s to 2010, total U.S. college enrollment nearly quadrupled, rising to a peak of 21 million students at the height of the Great Recession. Since then, the trend has reversed: enrollment declined steadily through 2019, fell more sharply during the COVID-19 years of 2020–21, and has recovered only modestly. In fall 2023, about 19 million students were enrolled—two million fewer than in 2010.imagine

The decline is an undergraduate story The overall post-2010 decline is driven entirely by falling undergraduate numbers. By contrast, graduate enrollment—just under 20 percent of total headcount—has inched upward. From 2010 to 2023, undergraduate enrollment fell from 18.2 million to 15.9 million, while graduate enrollment rose from 2.9 million to 3.2 million. Although the absolute number of graduate students continues to grow, their count has fallen relative to the flow of recent bachelor’s degree recipients, indicating a subtle shift in post-baccalaureate participation even without an outright contraction of the graduate sector.

Community colleges drove the drop, and For-Profits Collapsed

Higher education in the United States spans multiple types of institutions with different primary functions, student profiles, and degree portfolios. Distinguishing among these sectors is essential, because enrollment patterns have diverged across them.

The largest enrollment drop has occurred at public two-year colleges, commonly known as community colleges. These institutions draw predominantly local, often older students, award associate degrees and short-term certificates, and serve as a core component of U.S. workforce development.

Under the official IPEDS definitions, community-college enrollment fell by almost 40 percent, from 7.3 million in fall 2010 to 4.6 million in fall 2023. However, a meaningful share of this drop reflects reclassification rather than real attrition. Many two-year colleges now confer a small number of bachelor’s degrees without substantially altering their program mix. Because IPEDS assigns institutions to sectors based on the highest credential awarded, these schools are re-labeled as four-year institutions, shifting their students out of the two-year tally. Consequently, the apparent decline overstates the true enrollment loss in the community-college sector.

To remove reclassification effects, we follow institutions according to the sector in which they were classified in 2010. Under this fixed definition, community-college enrollment fell by just over 20 percent—from 7.3 million in 2010 to 5.6 million in 2023. The for-profit sector contracted even more sharply, dropping from 1.8 million to 0.6 million students, a decline that coincided with rising skepticism and stricter regulation of for-profit colleges.

In contrast, undergraduate enrollment at four-year institutions has remained relatively stable. Both public and private four-year colleges registered a modest COVID-19 enrollment dip, and the public four-year sector has yet to regain its pre-pandemic headcount.

Demographics play a role

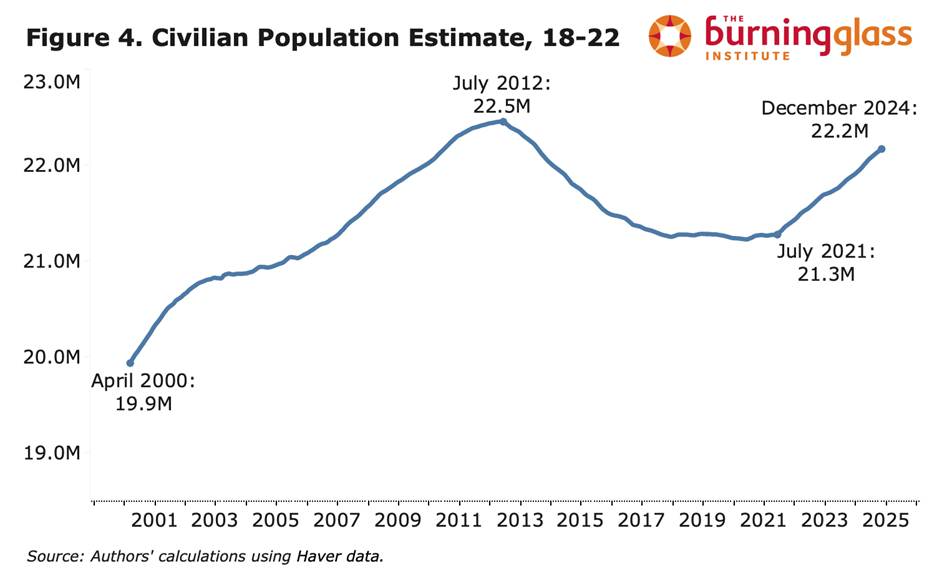

One of the biggest drivers of college enrollment is simply the size of the college-going age group. From 2012 to 2020, the number of 18–22-year-olds fell, which mechanically contributed to declining total enrollment.

The rebound you see after 2022 is largely explained by the surge in undocumentedimmigration. But since these young people are much less likely to enroll in college, the growth in headcount doesn’t necessarily translate into higher college enrollment.

4-year college enrollment rates stayed relatively constant. 2-year rates sharply declined.

Household survey data can complement our analysis of institutional enrollment counts and let us adjust for changes in the population’s age structure. Using the Current Population Survey (CPS), we track enrollment among 18- to 25-year-olds. CPS levels are not directly comparable to IPEDS counts: CPS is person-based, whereas IPEDS is institution-based. In addition, two-year enrollment—covering both associate programs and short-term certificates—is typically shorter and more likely to be part-time. CPS sector categories are self-reported rather than administrative, and the survey does not separate for-profit from non-profit institutions.

Despite these measurement differences, the CPS data paint a similar picture: two-year enrollment has fallen, while four-year and graduate enrollment have remained stable. The sharpest shift is a steady drop in the share of young adults attending community colleges. Notwithstanding a small uptick in enrollment at other institution types, most of the community-college decline reflects a rise in 18- to 25-year-olds who are not enrolled at all—a share that, after decades of decline, climbed from roughly 56 percent in 2010 to about 60 percent by 2023.

Degrees earned haven’t fallen with enrollment.

Falling enrollment prompts the question of how educational attainment is evolving—and with it, the future education composition of the labor force. To trace attainment levels, we again turn to household survey data, using the American Community Survey (ACS).

ACS data indicate that educational attainment among young adults has remained stable—and may even be rising. The share of 25-year-olds with only a high-school diploma or less has edged downward, as has the proportion with some college credit but no degree. By contrast, the fraction holding a bachelor’s or graduate degree has increased steadily.

Completion rates rose across the board

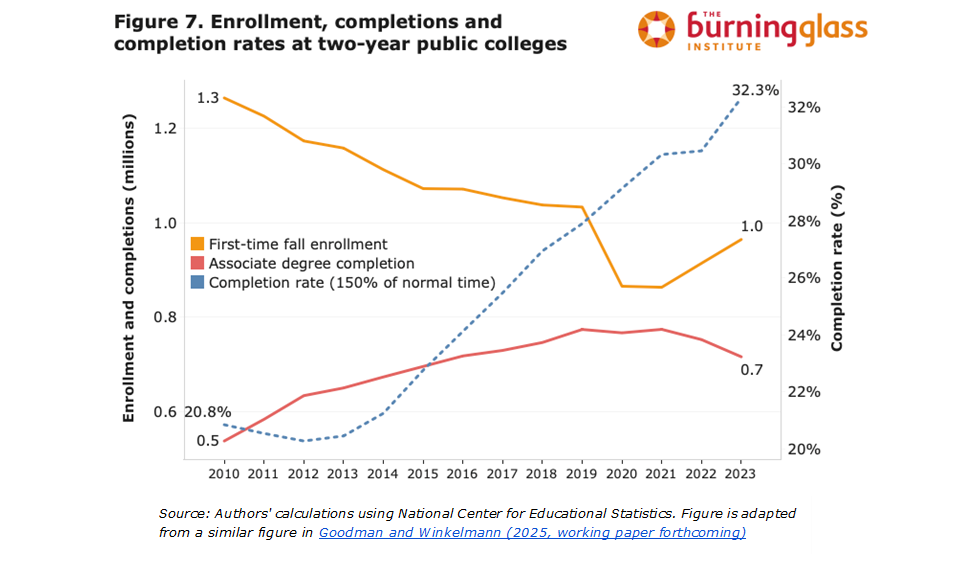

Community college enrollment has plummeted over the past decade. But the share of Americans with an associate degree—the credential most closely tied to these institutions—has barely changed. At first glance, that’s a puzzle.

How can degree attainment remain stable when fewer students are enrolling?

A big part of the answer lies in rising completion rates. Among full-time, first-time students in the two-year sector, the share graduating within 150% of program time has increased by more than 50% since 2010. So even with a shrinking pipeline, more students are finishing.

Why have completion rates improved?

At least two forces seem to be at work.

First, colleges got better at helping students succeed. Beginning in the early 2010s, many community colleges embraced a “completion agenda”: streamlining programs, replacing long remedial sequences, boosting advising, and offering practical supports like coaching and transportation. Some states tied funding to completions. Initiatives like CUNY ASAP showed that systemic reform could move the needle.

Second, the composition of who enrolls has likely shifted. As overall enrollment fell, some of the students least likely to finish—those facing greater academic or financial barriers—may have opted out altogether. That would mechanically raise completion rates among those who remain. Completion rates at four-year institutions have also risen in recent years, though the gains have been more modest—partly because rates at these institutions were already substantially higher to begin with.

Recent data suggest a continued recovery in enrollment.

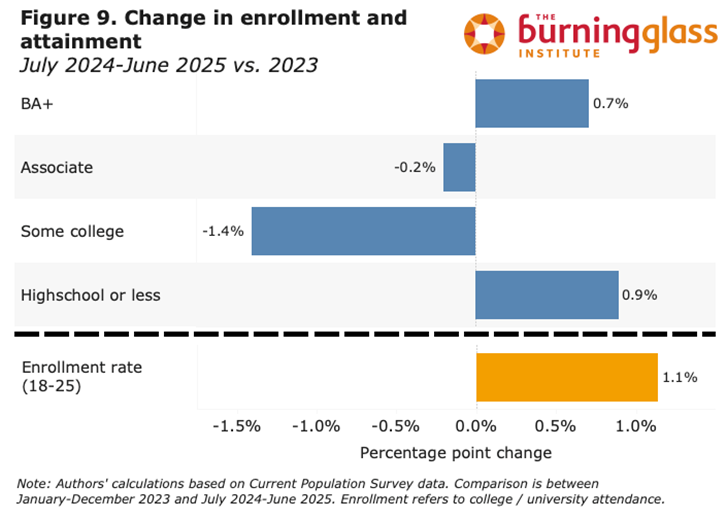

While our most detailed picture of U.S. higher education comes from institution-level IPEDS data, the CPS School Enrollment Supplement, and the ACS, all three sources arrive with a delay of more than a year. To assess more recent trends in college enrollment and educational attainment, we turn to the monthly CPS, comparing 2023 to the most recent 12-month period (July 2024–June 2025).

This analysis suggests that enrollment continues to rebound from its post-pandemic low. The share of 18–25-year-olds reporting current college or university enrollment is up by over one percentage point relative to 2023. However, the monthly CPS does not allow us to distinguish between different institution types (e.g., community colleges vs. four-year universities).

On the attainment side, we see signs of a widening educational split among young Americans. As Figure 5 shows, the share reporting “some college” as their highest level of education has been declining for over a decade—typically offset by more students earning degrees. But recent data suggest a change: while “some college” continues to shrink, about half of that decline is now being absorbed by a growing share of young adults whose highest credential is a high school diploma. This points to a possible post-pandemic stall in educational progression for some students.

Conclusion

Total college enrollment is much lower than in 2010. At first glance, the decline in U.S. college enrollment since 2010 paints a bleak picture. But that characterization is somewhat misleading for several reasons:

1. The decline is overwhelmingly an undergraduate phenomenon, concentrated in public two-year and for-profit institutions. Enrollment in other four-year institutions has remained broadly stable.

2. Demographics played a major role. The size of the 18–22 population shrank from roughly 2012 to 2021, mechanically pulling down total enrollment even though enrollment rates didn’t decline as sharply.

3. Completion rates have improved across sectors—especially in community colleges—reducing the “some college, no degree” group. Despite steep enrollment declines in community colleges, the share of Americans with an associate degree has held roughly steady, because more students are finishing. And the share of young Americans with a bachelor’s degree continues to rise.

Recent data through mid-2025 show a modest post-2023 rebound in enrollment among 18–25-year-olds. Degree attainment continues to inch upward for those with a BA or higher—even as the share with only a high school diploma has also risen slightly. Meanwhile, the “some college, no degree” category has fallen further, suggesting that more students are completing what they start, and fewer are dropping out midstream.

There is no evidence that young adults are becoming less likely to ultimately earn a college degree. Instead, a segment that previously would have enrolled in two-year colleges is choosing not to enroll at all. Given historically low completion rates in that group, some of this shift may reflect more efficient pathways—such as work, apprenticeships, or short non-degree training—rather than lost credentials.

Looking ahead, demographic pressures will intensify. The 18–22 population is set to contract again starting now, as the smaller birth cohorts from the post-2007 baby bust age into college. This will put renewed pressure on enrollment numbers, even if enrollment rates remain flat or improve—intensifying competition for traditional-age students.

An open question is whether the current difficulty many new graduates face in finding jobs they want will dampen interest in four-year colleges—nudging more students toward two-year programs, certificates, or work-first pathways—or instead increase demand for bachelor’s programs that embed stronger work-integrated learning and career placement.