Introducing: BGInsights

Featuring monthly research and insights from the Burning Glass Institute team.

The Long Game: How College Rankings Change Over the Career Lifecycle

This report examines how the long-term economic value of a college education evolves, focusing on the earnings trajectories of liberal arts college (LAC) graduates. While LAC alumni often earn less early in their careers—partly due to entering lower-paying, socially valuable fields—they tend to catch up over time, narrowing or closing the earnings gap with peers from other institutions. Using Burning Glass Institute’s comprehensive labor market data, the study explores how career mobility, graduate education, and generalist skills shape this catch-up, offering a more nuanced view of college rankings and long-term value.

By Gad Levanon, Joseph Winkelmann and Mels de Zeeuw

Introduction

Understanding the long-term economic value of a college education is a central concern for students, families, and policymakers. One popular approach to measuring this is through alumni earnings. These rankings typically rely on earnings measured just a few years after graduation.

The focus on early years can be especially damaging for liberal arts colleges (LACs). LAC graduates generally earn less than their peers, in part because they are more likely to enter lower-paying but socially valuable fields such as education, the arts, and nonprofit work. Especially after adjusting for student selectivity—using metrics like average SAT scores—graduates from LACs appear to dramatically underperform in early-career earnings. This depresses their position in school rankings and may reduce their appeal to prospective students.

However, much of this underperformance is concentrated in the early years after graduation. Over time, LAC graduates tend to catch up—narrowing or even closing the earnings gap with peers from other institutions. This report investigates how the earnings of different college types evolves from early to mid-career, with a particular focus on liberal arts colleges.

Using the Burning Glass Institute’s comprehensive labor market database, which contains career histories of over 65 million Americans and spanning multiple decades of graduates, we examine both the extent of this earnings catch-up and the factors that may drive it—including occupational mobility, graduate school enrollment, family background, and the long-term benefits of generalist skills.

By tracing these lifecycle dynamics, we aim to inform more nuanced college rankings and contribute to a deeper understanding of what makes a college education truly “valuable” over the course of a career.

Definition, sample and data

Our college sample includes all liberal arts colleges, public research universities, and private research universities in the US. We exclude other types of higher education institutions such as community colleges, for-profits, or professions-focused schools, as these institutions tend to attract different types of students. The institutions in our sample account for around 75% of bachelor’s degrees awarded in the US every year.

Among public and private research universities, we further distinguish high-STEM schools as schools with high shares of certain majors in their distribution of awarded degrees between 2010-2023.[1] We divide 562 schools into the following groups:

1. Liberal arts colleges (N=158)

2. High-STEM research universities (N=80)

3. Other public research universities (N=169)

4. Other private research universities (N=155)

Figure 1 shows how liberal arts colleges and STEM schools differ meaningfully in the programs they focus on and thereby also in the careers they prepare their students for. The figure shows the shares of awarded bachelor’s degrees by school type for distinct degree types. Liberal arts schools stand out as awarding noticeably low shares of business and other professional degrees. Instead, liberal arts schools award a comparatively high share of social science and humanities degrees.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Services (11), Engineering (14), Engineering Technologies/Technicians (15), Military Technologies (29), Science Technologies/Technicians (41)

These differences in specializations may contribute to differences in average earnings trajectories between colleges. In our main results below, we measure earnings differences between graduates of different colleges conditional on college major, in addition to demographic controls. Conceptually, we are interested in whether students who major in the same field will expect different earnings trajectories depending on the type of college they attend. We consider some potential reasons for such differences in our analysis and discussion below.

Our earnings measures are based on students who graduated with a bachelor’s degree between 1988 and 2023. We observe earnings outcomes between calendar years 2008 and 2024. Our main object of interest is the average value-add of these four groups of schools at different experience levels, which we define as years since graduation.

It is important to account for differences in average SAT scores.

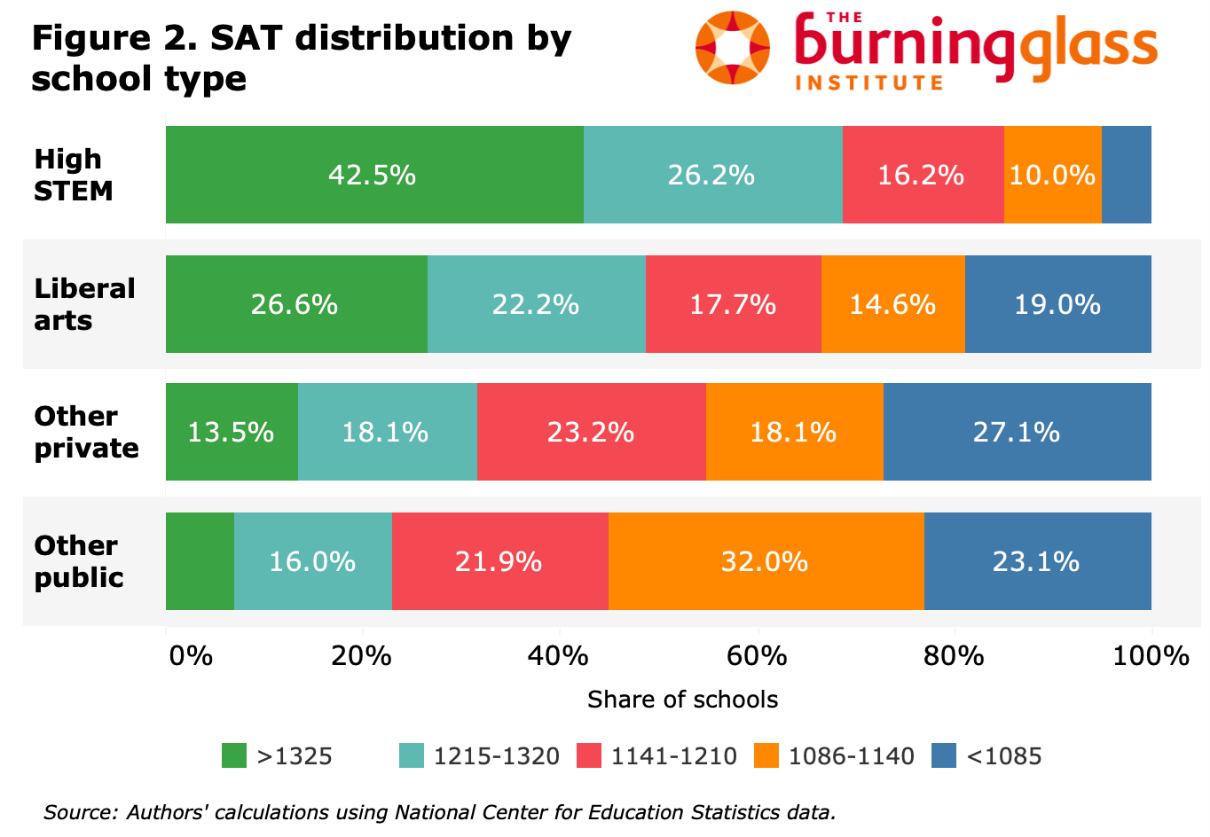

Before we get to the main results we need to account for differences in average SAT scores across colleges. Individual earnings depend on many factors, and there is differential selection of students across schools that limits the “value-add” interpretation when comparing raw graduate earnings. It is beyond the scope of our analysis to control for all such factors, but we do control for the average SAT score of admitted students. As Figure 2 shows, SAT scores vary significantly across school types—high-STEM schools are especially likely to admit high-scoring students. Therefore, we present results of our analysis also controlling for SAT to rule out that those differences are driving our findings.

Do Rankings Shift Over Time? Earnings Value-Add by Years Since Graduation

In order to understand differences in lifecycle earnings patterns across school types, we estimate value-add regressions separately by year since bachelor graduation. We regress log earnings on race, gender, degree major, cohort, and school fixed effects. We then average the school fixed effects within types of schools, both raw and controlling for the average SAT scores of admitted students. We exclude currently enrolled graduate students who may have artificially low earnings from part-time or similar jobs. Figure 3 shows the results from that analysis.

Liberal Arts Colleges Results

While this report focuses on changes over time, first-time Labor Matters readers may be surprised by how low the salary value-added is for graduates of liberal arts colleges (LACs). After controlling for SAT scores, LACs consistently rank lowest among the four groups across the entire career lifecycle.

One major reason is that LAC graduates are far more likely to pursue social-impact occupations—roles in fields like education, social services and non-for-profits that contribute to the public good but tend to pay less than other jobs requiring similar levels of education. These positions are vital to society yet remain undervalued in the labor market.

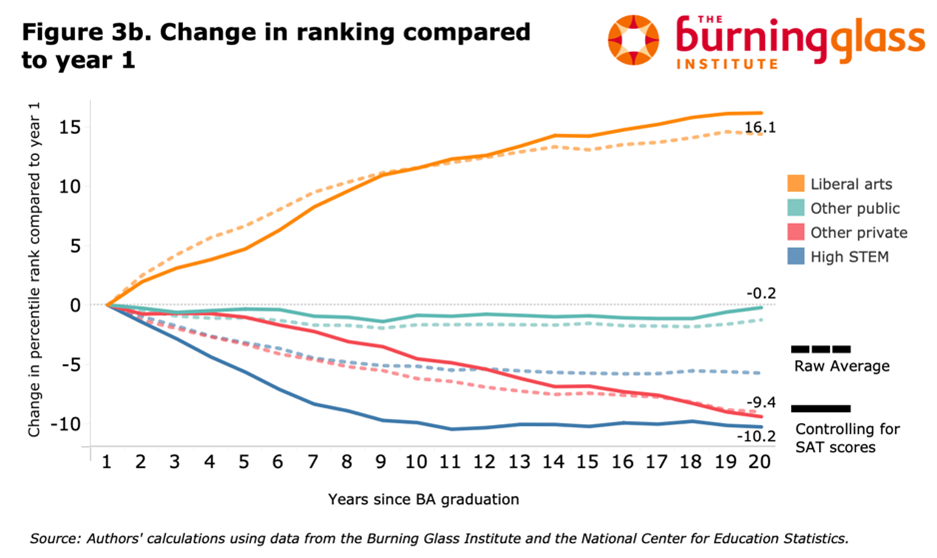

Turning to the over-time analysis, the blue line in Figure 3A shows that liberal arts graduates gradually catch up to the average graduate over time. This pattern is even clearer in Figure 3B, which tracks changes in the average percentile rank by school type relative to the first year after graduation.

As Figure 3 illustrates, graduates of liberal arts colleges gain roughly 15 percentile ranks between the first year after graduation and 15–20 years later. In the left-hand chart (without controlling for SAT), LACs start with the lowest value-add among the four groups but, by year 15, trail only the high-STEM group.

By contrast, graduates of high-STEM schools and private research universities look especially strong in the early years after graduation but lose some ground over time—even though they continue to earn the highest salaries on average. In general, the type of college one goes to matters much more at the beginning of one’s career than in the middle of it.

While Figure 3 compares general patterns between the different types of schools, Figure 4 shows the school-specific trends underlying these broad patterns for a select group of liberal arts colleges. These examples highlight how liberal arts colleges tend to significantly improve their value-add ranking over time, especially within the first decade or so after graduation.

What Could Be Driving the Earnings Catch-Up for Liberal Arts College Graduates?

We find that graduates of liberal arts colleges tend to earn less early in their careers but gradually catch up to peers from other institutions. What might explain this trajectory?

Our regressions already control for race, gender, and undergraduate major at the individual level, as well as average SAT scores by institution as a proxy for academic selectivity. Yet the narrowing wage gap over time suggests additional dynamics are at play.

1. Family Income and Wealth

Liberal arts college (LAC) students tend to come from significantly wealthier families than students at other types of institutions (Figure 5). This can influence earnings trajectories in multiple ways, notably through strategic early-career choices: Higher family income allows LAC graduates to accept lower-paying but prestigious early jobs (e.g., in nonprofits, research, or policy), which may yield higher long-run returns.

2. Graduate School Enrollment

Partly because of higher family wealth, graduates of liberal arts colleges (LACs) are far more likely to pursue graduate or professional degrees—a key reason for their delayed earnings growth. As shown in Figure 6, LACs have significantly higher graduate school enrollment rates than other institutions.

Graduate education shapes earnings in several ways. First, advanced degrees—especially in law, business, and medicine—substantially raise earnings after completion.

Second, graduate school enrollment is not random. If high-ability students are more likely to continue their education, early-career data may understate the earnings potential of LAC graduates, since many of their strongest students are temporarily absent from the labor market. As these individuals re-enter the workforce, LACs appear to “catch up” over time.

Other Potential Explanations

Beyond graduate school and family background, several career-related factors may help explain the earnings catch-up observed among liberal arts college (LAC) graduates:

Occupational Transitions: Many LAC graduates start their careers in mission-driven or social-impact roles that pay relatively little. Over time, however, they often move into higher-paying sectors such as consulting, policy, philanthropy, or tech-enabled services—especially as financial pressures grow.

Upward Mobility Within Fields: Even those who remain in lower-paying sectors frequently advance into management or leadership roles (e.g., a teacher becoming a principal or a nonprofit officer rising to executive director), which bring substantial pay increases.

Sector Shifts Without Occupational Change: Some LAC graduates remain in similar occupations but move from nonprofit or public organizations to private-sector roles—such as from a nonprofit policy analyst to a consulting firm—where compensation is typically higher.

Generalist and Transferable Skills That Appreciate Over Time: Liberal arts colleges emphasize broad, transferable skills—such as communication, critical thinking, and interpersonal ability—that become more valuable as careers progress. Even within technical majors, LAC programs tend to stress generalist training over narrow specialization, which may lead to steeper earnings growth over the career lifecycle, consistent with the arguments of Deming and Noray (2020).

Conclusion

Our analysis shows that timing plays a critical role in measuring the value-added of different college types. Liberal arts college (LAC) graduates tend to earn less in the early years after graduation, leading to lower rankings in salary-based comparisons—especially when controlling for student selectivity.

However, these same graduates show substantial earnings catch-up over time, gaining as much as 15 percentile points in ranking by year 15. This lifecycle dynamic reflects several factors such as higher rates of graduate school enrollment, and occupational and sectoral shifts into higher-paying or leadership roles. It may also highlight the growing value of transferable skills developed in liberal arts settings.

In contrast, high-STEM schools deliver strong early returns that level off over time. These findings suggest that rankings based on short-term earnings can misrepresent long-term outcomes, particularly for institutions like LACs whose graduates follow delayed career trajectories.

[1] We define high-STEM schools as private or public research universities that fall in the top quintile of the share of bachelor’s degrees awarded in the following areas (CIP codes): Computer and Information Sciences and Support Services (11), Engineering (14), Engineering Technologies/Technicians (15), Military Technologies (29), Science Technologies/Technicians (41)

[2] With these cohorts and earning years our base analysis is not balanced, but the patterns described here hold true if we restrict to a single group of cohorts to control for potential cohort effects.

College Numbers Down, Degrees Up: Understanding the Post-2010 Enrollment Shift

After peaking in 2010, U.S. college enrollment has fallen by about 2 million—even as degree attainment keeps rising. Our new analysis shows the decline is concentrated in community colleges and for-profits, driven partly by demographics, while four-year enrollment rates and completion—especially at two-year institutions—have strengthened. In this post, we unpack what’s really changing in higher ed and why it matters for students and states.

By Joe Winkelman, Gad Levanon and Mels de Zeeuw

After decades of expansion, American higher education has entered a period of contraction and reconfiguration. From the mid-1960s to 2010, college enrollment nearly quadrupled, reaching a peak of 21 million students. Since then, total enrollment has fallen by two million.

At first glance, this decline seems alarming. But a closer look reveals a more nuanced—and in some ways, encouraging—story.

Most of the decline is concentrated in undergraduate enrollment, particularly at community colleges. Four-year college enrollment has been more stable, and most of its losses came from the collapse of for-profit institutions. Demographics also played a role: as the 18–22 population shrank between 2012 and 2020, overall enrollment fell more dramatically than enrollment rates.

The good news: Enrollment rates at four-year colleges held firm. And thanks to rising completion rates, the share of young adults earning bachelor’s degrees continued to grow.

The surprising good news: Despite a steep drop in community college enrollment, associate degree attainment has not declined—because completion rates have improved dramatically.

In the pages that follow, we examine how and why these patterns emerged, with particular focus on the evolving role of community colleges. We also explore what these trends mean for the future.

A long era of enrollment growth came to an end in 2010.

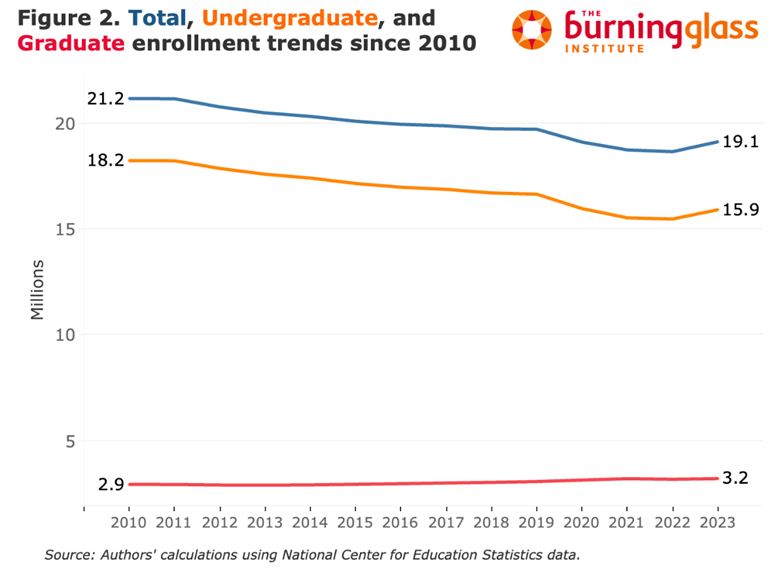

From the mid-1960s to 2010, total U.S. college enrollment nearly quadrupled, rising to a peak of 21 million students at the height of the Great Recession. Since then, the trend has reversed: enrollment declined steadily through 2019, fell more sharply during the COVID-19 years of 2020–21, and has recovered only modestly. In fall 2023, about 19 million students were enrolled—two million fewer than in 2010.imagine

The decline is an undergraduate story The overall post-2010 decline is driven entirely by falling undergraduate numbers. By contrast, graduate enrollment—just under 20 percent of total headcount—has inched upward. From 2010 to 2023, undergraduate enrollment fell from 18.2 million to 15.9 million, while graduate enrollment rose from 2.9 million to 3.2 million. Although the absolute number of graduate students continues to grow, their count has fallen relative to the flow of recent bachelor’s degree recipients, indicating a subtle shift in post-baccalaureate participation even without an outright contraction of the graduate sector.

Community colleges drove the drop, and For-Profits Collapsed

Higher education in the United States spans multiple types of institutions with different primary functions, student profiles, and degree portfolios. Distinguishing among these sectors is essential, because enrollment patterns have diverged across them.

The largest enrollment drop has occurred at public two-year colleges, commonly known as community colleges. These institutions draw predominantly local, often older students, award associate degrees and short-term certificates, and serve as a core component of U.S. workforce development.

Under the official IPEDS definitions, community-college enrollment fell by almost 40 percent, from 7.3 million in fall 2010 to 4.6 million in fall 2023. However, a meaningful share of this drop reflects reclassification rather than real attrition. Many two-year colleges now confer a small number of bachelor’s degrees without substantially altering their program mix. Because IPEDS assigns institutions to sectors based on the highest credential awarded, these schools are re-labeled as four-year institutions, shifting their students out of the two-year tally. Consequently, the apparent decline overstates the true enrollment loss in the community-college sector.

To remove reclassification effects, we follow institutions according to the sector in which they were classified in 2010. Under this fixed definition, community-college enrollment fell by just over 20 percent—from 7.3 million in 2010 to 5.6 million in 2023. The for-profit sector contracted even more sharply, dropping from 1.8 million to 0.6 million students, a decline that coincided with rising skepticism and stricter regulation of for-profit colleges.

In contrast, undergraduate enrollment at four-year institutions has remained relatively stable. Both public and private four-year colleges registered a modest COVID-19 enrollment dip, and the public four-year sector has yet to regain its pre-pandemic headcount.

Demographics play a role

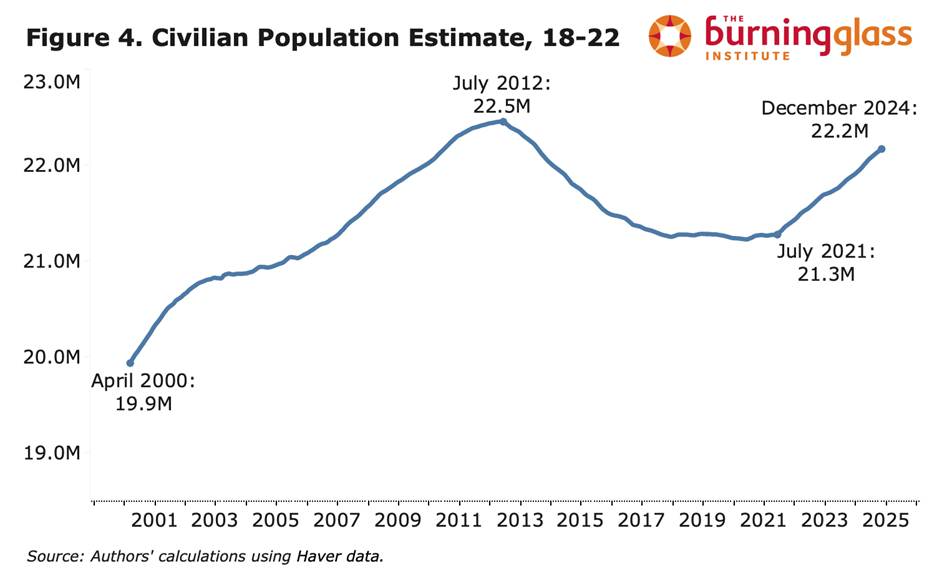

One of the biggest drivers of college enrollment is simply the size of the college-going age group. From 2012 to 2020, the number of 18–22-year-olds fell, which mechanically contributed to declining total enrollment.

The rebound you see after 2022 is largely explained by the surge in undocumentedimmigration. But since these young people are much less likely to enroll in college, the growth in headcount doesn’t necessarily translate into higher college enrollment.

4-year college enrollment rates stayed relatively constant. 2-year rates sharply declined.

Household survey data can complement our analysis of institutional enrollment counts and let us adjust for changes in the population’s age structure. Using the Current Population Survey (CPS), we track enrollment among 18- to 25-year-olds. CPS levels are not directly comparable to IPEDS counts: CPS is person-based, whereas IPEDS is institution-based. In addition, two-year enrollment—covering both associate programs and short-term certificates—is typically shorter and more likely to be part-time. CPS sector categories are self-reported rather than administrative, and the survey does not separate for-profit from non-profit institutions.

Despite these measurement differences, the CPS data paint a similar picture: two-year enrollment has fallen, while four-year and graduate enrollment have remained stable. The sharpest shift is a steady drop in the share of young adults attending community colleges. Notwithstanding a small uptick in enrollment at other institution types, most of the community-college decline reflects a rise in 18- to 25-year-olds who are not enrolled at all—a share that, after decades of decline, climbed from roughly 56 percent in 2010 to about 60 percent by 2023.

Degrees earned haven’t fallen with enrollment.

Falling enrollment prompts the question of how educational attainment is evolving—and with it, the future education composition of the labor force. To trace attainment levels, we again turn to household survey data, using the American Community Survey (ACS).

ACS data indicate that educational attainment among young adults has remained stable—and may even be rising. The share of 25-year-olds with only a high-school diploma or less has edged downward, as has the proportion with some college credit but no degree. By contrast, the fraction holding a bachelor’s or graduate degree has increased steadily.

Completion rates rose across the board

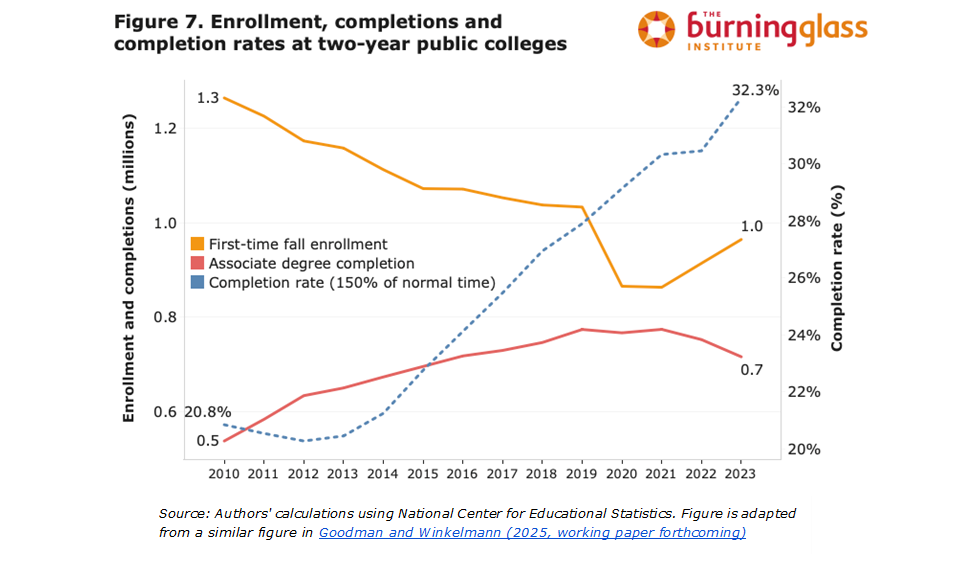

Community college enrollment has plummeted over the past decade. But the share of Americans with an associate degree—the credential most closely tied to these institutions—has barely changed. At first glance, that’s a puzzle.

How can degree attainment remain stable when fewer students are enrolling?

A big part of the answer lies in rising completion rates. Among full-time, first-time students in the two-year sector, the share graduating within 150% of program time has increased by more than 50% since 2010. So even with a shrinking pipeline, more students are finishing.

Why have completion rates improved?

At least two forces seem to be at work.

First, colleges got better at helping students succeed. Beginning in the early 2010s, many community colleges embraced a “completion agenda”: streamlining programs, replacing long remedial sequences, boosting advising, and offering practical supports like coaching and transportation. Some states tied funding to completions. Initiatives like CUNY ASAP showed that systemic reform could move the needle.

Second, the composition of who enrolls has likely shifted. As overall enrollment fell, some of the students least likely to finish—those facing greater academic or financial barriers—may have opted out altogether. That would mechanically raise completion rates among those who remain. Completion rates at four-year institutions have also risen in recent years, though the gains have been more modest—partly because rates at these institutions were already substantially higher to begin with.

Recent data suggest a continued recovery in enrollment.

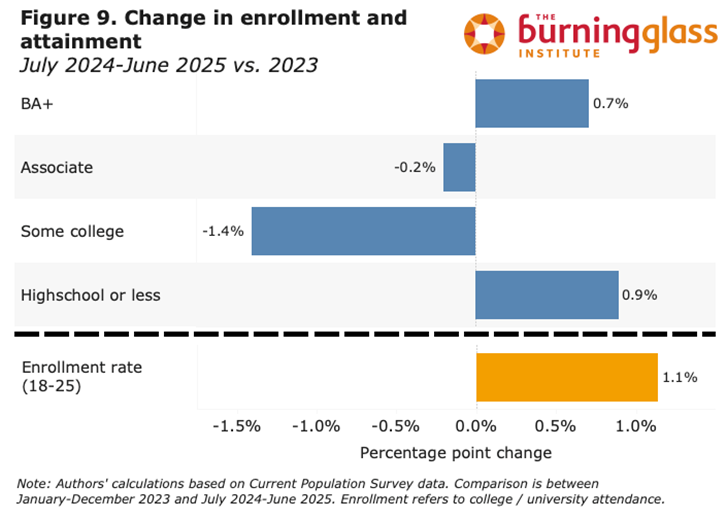

While our most detailed picture of U.S. higher education comes from institution-level IPEDS data, the CPS School Enrollment Supplement, and the ACS, all three sources arrive with a delay of more than a year. To assess more recent trends in college enrollment and educational attainment, we turn to the monthly CPS, comparing 2023 to the most recent 12-month period (July 2024–June 2025).

This analysis suggests that enrollment continues to rebound from its post-pandemic low. The share of 18–25-year-olds reporting current college or university enrollment is up by over one percentage point relative to 2023. However, the monthly CPS does not allow us to distinguish between different institution types (e.g., community colleges vs. four-year universities).

On the attainment side, we see signs of a widening educational split among young Americans. As Figure 5 shows, the share reporting “some college” as their highest level of education has been declining for over a decade—typically offset by more students earning degrees. But recent data suggest a change: while “some college” continues to shrink, about half of that decline is now being absorbed by a growing share of young adults whose highest credential is a high school diploma. This points to a possible post-pandemic stall in educational progression for some students.

Conclusion

Total college enrollment is much lower than in 2010. At first glance, the decline in U.S. college enrollment since 2010 paints a bleak picture. But that characterization is somewhat misleading for several reasons:

1. The decline is overwhelmingly an undergraduate phenomenon, concentrated in public two-year and for-profit institutions. Enrollment in other four-year institutions has remained broadly stable.

2. Demographics played a major role. The size of the 18–22 population shrank from roughly 2012 to 2021, mechanically pulling down total enrollment even though enrollment rates didn’t decline as sharply.

3. Completion rates have improved across sectors—especially in community colleges—reducing the “some college, no degree” group. Despite steep enrollment declines in community colleges, the share of Americans with an associate degree has held roughly steady, because more students are finishing. And the share of young Americans with a bachelor’s degree continues to rise.

Recent data through mid-2025 show a modest post-2023 rebound in enrollment among 18–25-year-olds. Degree attainment continues to inch upward for those with a BA or higher—even as the share with only a high school diploma has also risen slightly. Meanwhile, the “some college, no degree” category has fallen further, suggesting that more students are completing what they start, and fewer are dropping out midstream.

There is no evidence that young adults are becoming less likely to ultimately earn a college degree. Instead, a segment that previously would have enrolled in two-year colleges is choosing not to enroll at all. Given historically low completion rates in that group, some of this shift may reflect more efficient pathways—such as work, apprenticeships, or short non-degree training—rather than lost credentials.

Looking ahead, demographic pressures will intensify. The 18–22 population is set to contract again starting now, as the smaller birth cohorts from the post-2007 baby bust age into college. This will put renewed pressure on enrollment numbers, even if enrollment rates remain flat or improve—intensifying competition for traditional-age students.

An open question is whether the current difficulty many new graduates face in finding jobs they want will dampen interest in four-year colleges—nudging more students toward two-year programs, certificates, or work-first pathways—or instead increase demand for bachelor’s programs that embed stronger work-integrated learning and career placement.

Who’s Still Quitting? The Uneven End of the Great Resignation

By Gad Levanon and Mels de Zeeuw

The quits rate is a key barometer to understand the labor market. It’s a key proxy for labor-market tightness and hiring difficulty, closely watched by employers. Because quits capture how often workers voluntarily leave, they signal how costly it will be for firms to recruit, train, and bring new employees up the learning curve—costs that translate into lost productivity and higher replacement expenses. When quits remain subdued, companies feel less pressure to keep workers happy through higher pay, flexible schedules, or generous benefits, since the risk of losing talent is lower.

Every month the Job Openings and Labor Turnover (JOLTS) survey from the Bureau of Labor Statistics provides data on quits, separations, and layoffs, which allows us a timely look on whether employers are facing a tight labor market, or whether their workers’ employment positions are worsening.

However, while JOLTS is great for national, industry and state trends, it can’t tell us who is doing the switching and doesn’t offer data by occupation, education, age, or race/ethnicity. Building on Bart Hobijn’s approach, we link CPS microdata to JOLTS to estimate quits, layoffs, and total separations for detailed worker groups. That matters because knowing which groups are quitting shows exactly where the pressure is, and where it isn’t.

Methodology

To estimate quits rates by non-JOLTS demographics such as age, occupation, or educational attainment, we use microdata from the Current Population Survey’s monthly survey. We first determine whether workers in each month transitioned from one employer to the next, or from their job into unemployment or out of the labor force; and whether they did so voluntarily or involuntarily. For some respondents we could identify a separation, but not the reason behind it. Quits, layoffs, and indeterminable sum to total separations.

Next, we created monthly averages for these three measures by industry, and anchored these to the equivalent seasonally adjusted JOLTS industry-level metrics to create adjustment factors. For each month and 2-digit NAICS industry combination we apply the factors to the CPS weights so adjusted measures of quits, layoffs, and separations match JOLTS at the industry level. This then allows us to analyze these rates by a variety of other demographic data present in the CPS.

To adjust for low observations counts and seasonal biases, we present results as 12-month moving averages, and omit demographic sub groups with too few observations to draw meaningful conclusions. This does mean turning points may appear with a lag. Finally, we’ve calculated both the rates, as well as the change in these rates from their peak in March 2022 during the Great Resignation, and expressed each month’s value as a percentile of that groups rates over the entire almost 24 year timeframe. We present some of this analysis below.

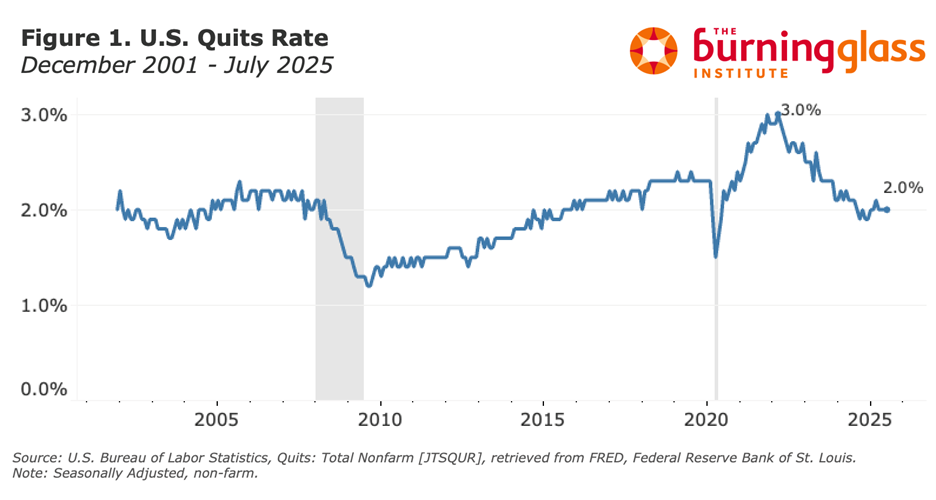

From the ‘Great Resignation’ back down to reality

As Figure 1 shows, resignations among workers rose steadily during the 2010 through 2019 period, dropped sharply during the COVID recession, before rising sharply and peaking in March 2022 in the period dubbed the ‘Great Resignation’. Since then, the quits rate has dropped steadily before stabilizing somewhat in 2025.

While the quits rate is still well above the lows of the Great Recession, in July 2025 it was below the historical norm, at its 42nd percentile. It remains to be seen whether resignation levels will stabilize or decline further, but clearly workers’ bargaining power has worsened in the past three years. However, as we will show, these declines have not occurred evenly across the board. We find a striking divergence in quits rate trends between young and older workers, between those with lower- and higher educational attainment, and between white- and blue-collar workers.

No country for young bargainers

As figure 2 shows, younger workers exhibit increasingly lower rates of resignation. While quits rates have declined among workers in all age groups, drops have been largest among those below the age of 40. Workers between 16 and 24 years old in particular are experiencing historically tight conditions, with their July 2025 quits rate being among the bottom quartile of the prior two and a half decades, and the lowest since December 2014.

Divergence by educational attainment

Figure 3 depicts trends in quits rates by educational attainment. Workers with less educational attainment have historically elevated quits rates compared to the prior two and a half decades (60-69th percentile). The notable exception occurs among workers with occupational/vocational associate’s degrees, which have a historically smaller churn (45th percentile).

The segment of workers with college degrees have resignation rates that are historically quite low. This is particularly striking among workers with PhDs (3rd percentile), where their quits rate in July 2025 marks one of the lowest months in the past 25 years. The last time the PhD quits rate was this low was April 2014.

It appears retention for Master’s and PhD graduates is currently relatively easy, while though easing it remains comparatively difficult to retain blue-collar workers. Given declining numbers of non-college educated workers, and a growing number individuals who are college educated, we can expect this divergence to persist.

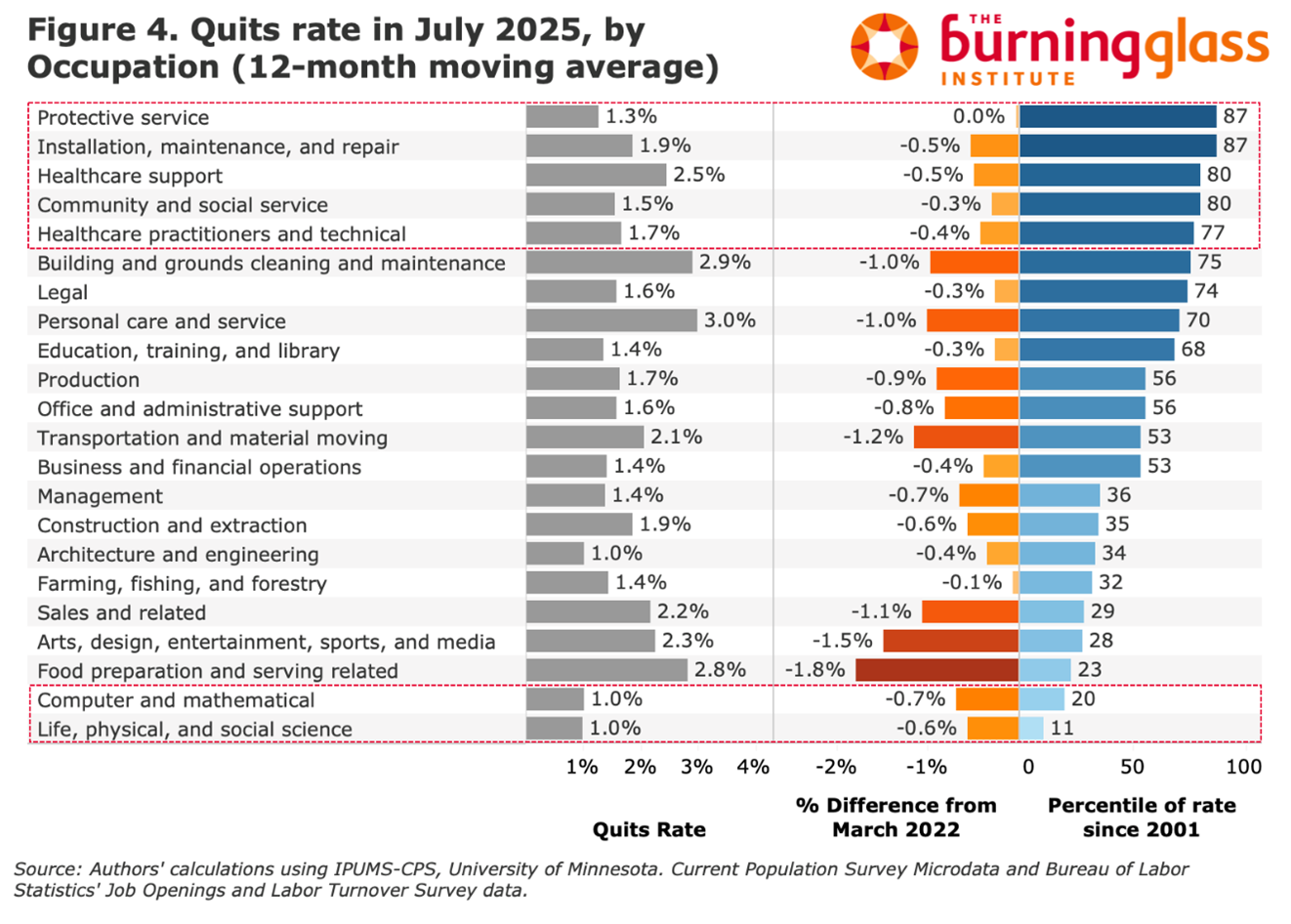

A two-track labor market: diverging occupation trends

As figure 4 illustrates, this historical trend in quits rates shows sharply diverging trends by occupation. Various blue-collar skilled, hands-on, and licensed roles remain historically hot. Quits rates among workers in Protective Services (87th percentile); Installation, Maintenance, and Repair (87th); among Health-care support and Community and Social Service roles (like social workers and counsellors) rates are at their 80th percentile; and among Health-care practitioners they are at their 77th percentile. On the other hand, quits rates are at near-historic lows among white-collar workers in Computer and Mathematical occupations (20th percentile); and in Life, Physical and Social Science jobs (11th percentile).

The results show some signs of a two-track labor market, wherein white-collar workers in Computer and Life/Physical/Social Science occupations have some of their lowest resignation rates in the past two decades; whereas conditions are tighter for employers in blue-collar installation and healthcare occupations.

Conclusion

While the Great Resignation is clearly over in aggregate, that conclusion masks important variation across the labor market. In July 2025, the national quits rate stood at around 2.0%, placing it at the 42nd percentile of the past 25 years—a clear sign that overall worker bargaining power has weakened from pandemic-era highs. However, newly developed demographic-specific quits measures—linking CPS microdata to JOLTS benchmarks—reveal a much more uneven picture beneath the surface.

To better capture these divergences, we analyzed not just raw quits rates but historical percentiles, comparing today’s values to each group’s own experience since 2001. This approach highlights whether quits are unusually high or low relative to each group’s history, offering a more accurate view of labor market strength.

Several patterns emerge. Younger workers are quitting at relatively low rates, reflecting historically weak bargaining positions compared to older age groups. Workers with advanced degrees are easier to retain than at almost any point in the past quarter century, while employers continue to face elevated churn among less-educated workers. White-collar jobs show lower turnover, whereas manual and blue-collar occupations still experience heightened churn. These patterns reflect a deeper mismatch in labor supply and demand, particularly across education levels and age groups.

On one side of the labor market, the supply of non-college workers is shrinking. Boomer retirements have been concentrated in blue-collar and manual service occupations, and tighter immigration—especially reduced undocumented inflows—has made replacement harder. College graduates rarely transition into these roles, so the labor pool for occupations in construction, food service, health support, maintenance, and logistics continues to thin. At the same time, demand for manual labor has remained steady—or even strengthened—in many sectors, helping to keep quits historically elevated in these occupations despite broader cooling.

On the other side, the number of college graduates continues to rise. This expanding supply is colliding with technological shifts, as generative AI automates routine analytical tasks and employers become more selective in hiring. Entry-level white-collar jobs have become the margin of adjustment, while employers increasingly favor experienced hires. The result is historically low quits among college graduates, especially those with advanced degrees. However, one puzzling finding remains: workers with graduate degrees are quitting at even lower rates than those with only a bachelor’s degree, a divergence that current explanations—supply growth, automation, or hiring shifts—do not fully account for.

Shifting Demographic and Education Trends and Their Impact on the U.S. Workforce

Boomer retirements are freezing overall headcount, but our research shows a different kind of churn: bachelor’s-degree holders are still climbing while the non-college workforce—especially women in hands-on roles—shrinks fast. That could leave us with surplus grads just as generative AI cools white-collar hiring, and a scramble for nurses, machinists, and carpenters who can’t be automated or offshored.

By Gad Levanon and Frank Steemers

America’s labor market is undergoing a structural shift, and our report projects how this will unfold across gender and education. With Boomer retirements accelerating and immigration only partially offsetting the decline, the working age population is no longer growing. Yet nearly every net addition in the coming years will have a bachelor’s degree.

By 2034, we project that the non-college population will be significantly smaller, while the number of degree holders continues to grow steadily. This raises the risk of a graduate surplus, especially as generative AI dampens white-collar job growth.

The gender dimension makes the imbalance even sharper. Our projections show that college-educated women will continue to surge, while non-college women, the core workforce for care, service, and support roles, decline rapidly. These are jobs that can’t be automated, offshored, or done remotely. As a result, hospitals, factories, and construction sites will face intensifying competition for the shrinking pool of hands-on workers.

The Slow Squeeze on America’s Workforce

It’s well known that the U.S. working-age population (ages 18–64) is barely growing—and that this stagnation will likely persist for at least the next decade. From 2017 onward, annual growth has slipped below 0.2%, a dramatic break from the 1–2% pace that characterized much of the 20th century. The chart shows why.

In the early 2000s, far more 17-year-olds were aging into prime-working age than 64-year-olds were aging out, adding nearly a full percentage point to labor-supply growth. In recent years, As the last Baby Boomers retire and the smaller Gen-Z cohorts replace them, that orange aging line essentially reaches zero.

The red migration line reflects an annual contribution of about 0.15 to 0.20 percentage points in the Census Bureau’s low-immigration scenario. Why focus on the “low” scenario?

This projection comes from the Census Bureau’s 2023 National Population Projections, which offer several immigration pathways. We chose the low-immigration variant to illustrate what could happen if U.S. policy shifts toward a more restrictive approach, similar to the Trump-era policies that sharply reduced refugee admissions and tightened border enforcement. Such a shift is plausible following the surge in undocumented immigration between 2022 and 2024.

The grey line tracing overall prime-age growth slides from more than 1% in 2000 to near-zero through 2035. Under present, low-immigration assumptions, the United States is entering a decade, or more, of flat or shrinking prime-age labor supply.

Chart 1

However, a much less reported, but perhaps more consequential, trend is underway beneath the surface.

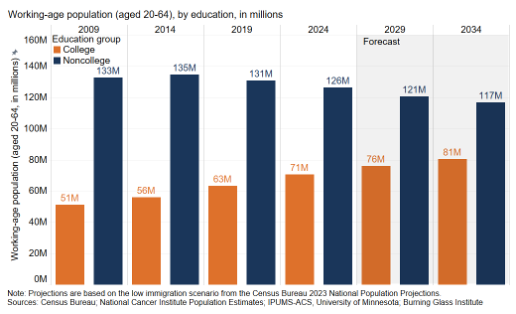

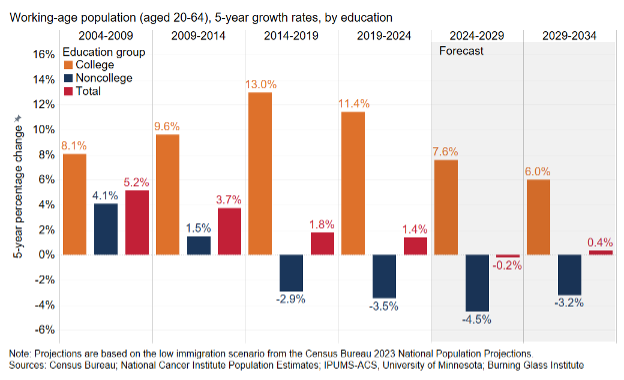

The decline in the working-age population (ages 20–64) applies only to those without a college degree. In contrast, the number of working-age people with a bachelor’s degree has been rising consistently and steadily—and is projected to continue growing at 1–1.5% annually through at least 2035 (Charts 2 and 3).

Chart 2

Chart 3

Why? Because the rising generation of young adults is far more likely to hold a bachelor’s degree than the retiring cohorts they’re replacing. That compositional shift is reshaping labor supply, not just in size but in kind.

And it matters. People with a bachelor’s degree typically avoid blue-collar and manual services occupations, roles in transportation, production, construction, farming, maintenance and repair, food services, cleaning, security, personal care, and health support. As a result, the supply of available workers in those roles is shrinking, and will continue shrinking in the decade ahead.

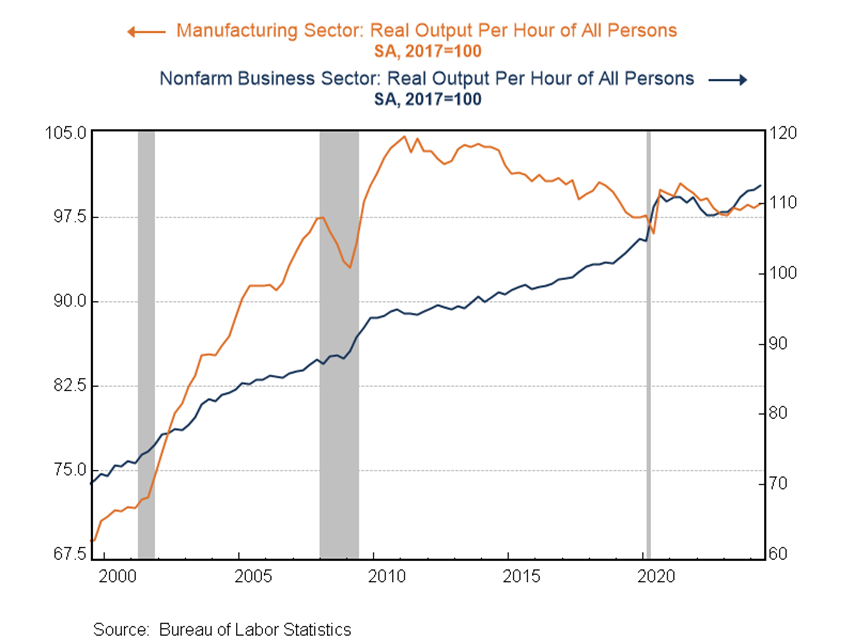

That’s a problem, because demand for blue-collar and manual service workers remains strong and in many cases is rising (Chart 4). Despite the steady expansion of the knowledge economy and white-collar employment, manual jobs have proven far more resilient than many expected.

Chart 4

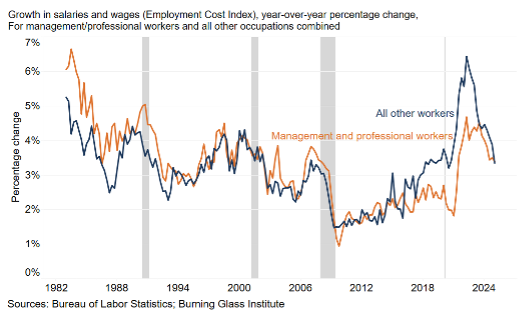

As a result, in recent years labor shortages were more severe, and wage growth was higher, in blue-collar and manual services jobs than in white-collar ones, a complete reversal from the dominant pattern of recent decades, where employers struggled most to hire workers with college degrees.

Chart 5

Yet that backdrop of demographic scarcity collides with another force moving at rapid speed: generative AI and other productivity improving factors are starting to erode the very white-collar headcount that once seemed scarce.

For the labor market this means that a continuation of the existing trend: the pinch point will be blue collar and manual services jobs. Jobs our aging population still needs but AI can’t yet nail, while many college-pathway office jobs will see slower hiring and flatter wages. Over time that shift could further compress the college wage premium.

A Gender Divide: Steeper Declines Among Non-College Women

The shrinking non-college workforce is being driven disproportionately by women. Over the past decade, the number of working-age women without a bachelor’s degree has declined far more steeply than men. Projections suggest this gap will widen, creating growing imbalances in frontline service jobs that rely heavily on non-college female labor.

At the same time, women continue to outpace men in higher education. College-educated women now significantly outnumber college-educated men—and that lead is expected to grow.

This shift has major implications. As non-college women exit the labor pool, care-focused sectors like healthcare support, childcare, and personal care face acute staffing pressure. These hands-on roles can’t easily be automated and will need to adapt—by boosting wages, improving job quality, or expanding recruiting pipelines—to keep up with demand.

Chart 6

Conclusion

Demography and education are steering the labor market toward an odd equilibrium: too many degree holders, too few hands-on workers. Employers in transport, trades, and care will confront chronic vacancies and rising wages, spurring automation and pressuring policymakers to expand vocational pathways, immigration, and participation incentives. Conversely, an oversupply of graduates, particularly women, could flatten starting salaries The gender wrinkle matters: frontline sectors most starved for labor draw heavily from the very group of non-college women disappearing fastest.

Methodology for the Population Projections by Education

This analysis creates education-specific population projections using a methodology consisting of three main components:

Population Data Integration and Calibration

The analysis begins by integrating historical population estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau (through 2024) with the official 2023 national population projections. These datasets are harmonized using a growth rate calibration function that ensures smooth transitions between the historical and projected periods while maintaining consistency with the most recent available data. The analysis relies on the “low” immigration projection scenario.

Education Data Distribution

Educational attainment patterns are derived from the American Community Survey, which provides information on educational attainment by age, sex, and year. The analysis classifies education into two categories: below BA and BA and above. Education shares are calculated for each 5-year age group and gender up to 2024.

Projection Approach

The analysis employs two complementary projection methods, each suited to different age groups and time horizons:

Cohort Change Ratio (CCR) Method: Applied to older age groups (30+ years), this method tracks how each 5-year age/gender/education group evolves as cohorts age over 5-year periods. The CCR is calculated as the ratio of the population in each group in 2024 (e.g., women with a BA aged 45–49) to the same cohort’s size in 2019 (e.g., women with a BA aged 40–44). The observed pattern (CCR 2019–2024) is applied to estimate the education-specific population in 2029 and 2034.

Constant Method: Used for younger age groups (under 30), this approach assumes that education shares remain constant after 2024. This reflects the reality that many younger individuals have not yet completed their education. The CCR method for these younger age groups was found to be too volatile.

The resulting education-specific population estimates are then calibrated to match the total population projections from the Census Bureau, ensuring consistency with official demographic projections.

Brains From Abroad: How U.S. Regions Compete for STEM Talent from Asia

For U.S. metro areas aspiring to grow as centers of innovation, the ability to attract highly educated international workers is not a luxury—it’s a necessity. Highly educated professionals from Asia now comprise a substantial share of the STEM workforce in leading American metros. At the Burning Glass Institute, we set out to quantify just how significant these workers are—and to proxy for the quality of the human capital they bring to different parts of the country. No other public source offers this kind of granular view at the national level of talent educated in Asia.

For U.S. metro areas aspiring to grow as centers of innovation, the ability to attract highly educated international workers is not a luxury—it’s a necessity. Highly educated professionals from Asia now comprise a substantial share of the STEM workforce in leading American metros. At the Burning Glass Institute, we set out to quantify just how significant these workers are—and to proxy for the quality of the human capital they bring to different parts of the country. No other public source offers this kind of granular view at the national level of talent educated in Asia.

We defined "Asia-educated" workers as individuals whose first bachelor's degree was from one of the 501 Asian universities featured in the QS World University Rankings. We then tracked the profiles of Asia-educated workers who are currently based in the U.S., identifying their locations by metropolitan statistical area (MSA).

To create a measure of talent quality, for each MSA, we computed a weighted average of the Asian universities QS rankings represented. Importantly, we adjusted this metric by controlling for the occupational mix of the Asia-educated workforce in each metro. This allowed us to avoid over-representing MSAs with a high concentration of tech or finance roles—industries that tend to attract graduates from more prestigious institutions in Asia.

Our findings show some clear patterns. In places like San Jose metro area, nearly one in five degree-holders were educated in Asia. Among tech workers, the figure rises above one in three. These professionals are not only numerous, but they are also highly credentialed, with many graduating from top-ranked institutions across Asia. While not to the same extent as Silicon Valley, tech hubs like the Bay Area and Seattle also rely heavily on highly credentialed talent from Asia.

But our data shows that other regions are clearly falling behind. In metros such as Miami—as well as much of the South and the Midwest, the share of STEM workers educated in Asia is lower, and the average ranking of their alma maters lags well behind that seen in coastal tech hubs.

The presence of Asia-educated workers follows clear regional patterns, with significant concentrations in both well-established tech hubs and some less expected manufacturing and academic centers. This uneven distribution reflects—and has the potential to reinforce—wider regional disparities. Areas that can integrate into global talent networks today will extend their lead in innovation and growth in the future. Others risk falling further behind.

Table 1 – Top 20 Asian universities according to QS World University Rankings

Mapping Asia-educated college grads in the U.S.

Asia-educated workers in the U.S. are primarily concentrated in the West and Northeast. Leading the way is Washington State, where 5.7% of all workers with at least a bachelor's degree were educated in Asia. California follows closely at 5.3%, with New Jersey, Massachusetts, Delaware, and New York hovering around 3%. These concentrations reflect regional economies that attract skilled talent in specialized industries. Texas follows with a share of 2.7%.

Figure 1

Asia-educated talent powering U.S. tech hubs

Zooming in from the state to the metro are level, tech-heavy regions stand out as prime destinations for Asia-educated professionals. Silicon Valley leads the pack: in the San Jose–Sunnyvale–Santa Clara metro, 18.7% of degree holders obtained their first BA from an Asian university. Other major tech hubs also rank high—8.3% in San Francisco–Oakland–Fremont and 7.1% in Seattle–Tacoma–Bellevue. A key driver of this pattern is the dominance of computer and mathematical occupations in these regions. Between 21% and 36% of tech workers with a degree in these MSAs were educated in Asia at the undergraduate level, underscoring the talent demands of major technology firms (see Figure 3).

Just as important, the average rank of their alma maters is significantly above average (see Figure 4), underscoring that Silicon Valley is importing not only numbers but top-tier credentials. In the tech centers of New York and Boston, the share of Asia-educated workers in computer and mathematical occupations is less than half that of San Francisco or Seattle, and about one third that of San Jose’s. Similarly, the average rank of the Asian universities attended by workers located in those metros tends to be somewhat lower (see Figure 4). New York and Pittsburgh stand out as the two East Coast’s metro areas with the highest quality scores. Boston, Providence and Baltimore rank lower (see Figure 4).

The South, however, scores even worse on our university attended quality score. While Texan metropolitan areas like Austin, Dallas, and Houston show shares of Asia-educated tech workers on par with that of the East Coast’s hubs—ranging from 2.8% to 3.4% (see Figure 2)— their average quality score is lower. Atlanta fares even worse. Finally, among large metros with a noteworthy tech presence, Miami is the outlier. Only about 1.0% of tech workers in the metro are Asia-educated, and those who tend to have attended lower-ranked Asian universities as well.

The Midwest shows a similar pattern to most of the South, with generally low shares of Asia-educated workers across most states (see Figure 1). Illinois leads the region at 2.2%, but Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and Minnesota all fall below the national average of 2.3%. While Chicago stands out as a partial exception, most of the region struggles to attract Asia-educated STEM talent—both in numbers and in the average rank of universities they attended. A few places buck the trend—Columbus, IN and college towns like West Lafayette and Ann Arbor—but for much of the Midwest, limited access to global talent could constrain future innovation and growth.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Beyond software: Asia-educated talent in engineering

The picture shifts only slightly when we move away from computer and mathematical occupations and focus on architecture and engineering occupations—a category that includes STEM roles such as architects, aerospace engineers, and industrial engineers. These are professionals who may be involved in actual manufacturing processes but are just as likely to work in R&D, product design, prototyping, or other non-manufacturing functions. Once again, Silicon Valley, the Bay Area, and tech hubs like Austin feature prominently. Asia-educated individuals account for 30.1% of all architecture and engineering workers in the San Jose metro, 16.0% in the San Francisco-Oakland-Fremont area, and 10.6% in Austin (see Figure 3). As highlighted before, while Silicon Valley mainly attracts talent educated in top Asian universities, this is less true for Austin. With a share of only 5.7% Seattle appears much further down the list this time, making it a secondary hub for engineering jobs. The engineers who do move to Seattle though tend to come from highly ranked Asian universities (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Looking beyond the top three MSAs by share of Asian-educated talent working in architecture and engineering, Portland, Detroit, Sacramento, and Phoenix stand out, with shares of Asia-educated talent making up from 6.8% to 8.7% of the local architecture and engineering workforce (see Figure 3). Of those metros, only Portland fares relatively well also on our quality score—as proxied by the average QS ranking of the universities they attended—performing on par with L.A. or Boston (see Figure 4). The other engineering hubs—namely Detroit, Sacramento, and Phoenix—tend to attract talent coming from lower-ranked Asian universities. This reflects how both traditional and up-and-coming advanced manufacturing hubs rely on technical talent educated in Asia. Portland and Phoenix are now established semiconductor manufacturing hubs, while Phoenix is also home to the headquarters of onsemi (ON Semiconductor Corporation). Detroit, for its part, has long been a national center of automotive engineering and manufacturing. Sacramento, while less industrial, plays a key role in public infrastructure, energy systems, and aerospace.

Beyond large metros: unique regional specializations

While large metros and major tech hubs consistently rely on Asia-educated talent to fill their STEM roles, many smaller metro areas with distinctive economic profiles have also emerged as magnets for this workforce. Columbus, IN is a striking example: graduates of Asian universities make up 8.6% of its college-educated workforce—a higher share than in the Bay Area or Seattle (see Figure 5). What’s driving this? Columbus is home to the global headquarters of Cummins Inc., a major player in engine manufacturing and power technologies. That helps explain the unusually high demand for engineering talent. Nearly half (46.1%) of Asia-educated workers in Columbus are employed in architecture and engineering occupations—the highest concentration across all metro areas. While Columbus punches above its weight when it comes to the share of Asia-educated talent, it scores below average on our quality score.

Figure 5

Figure 6

Another noteworthy pattern emerges in college towns. In metros such as Champaign-Urbana, IL (University of Illinois), Trenton-Princeton, NJ (Princeton University), Lafayette-West Lafayette, IN (Purdue University), Ithaca, NY (Cornell University), College Station-Bryan, TX (Texas A&M), State College, PA (Penn State University), Ann Arbor, MI (University of Michigan) and Ames, IA (Iowa State University) Asia-educated workers make up between 4.1% and 7.5% of the college-educated workforce (see Figure 5). That’s higher than in large metros like New York or Boston, and only slightly below levels seen in Seattle or San Francisco. Unsurprisingly, the presence of world-class academic institutions is a major driver: roughly one in two Asia-educated workers in these college towns are employed in academia. The academic pull is also visible in terms of quality: places like Ithaca, Champaign-Urbana, and Ann Arbor attract Asia-educated workers from top-ranked universities, on par with those found in major tech hubs like San Francisco or Seattle (see Figure 6). This reinforces a broader theme: specialized industries and elite research institutions—even outside traditional tech corridors—can exert a strong gravitational pull on international talent.

Conclusion

For American regions hoping to compete as tech and innovation hubs, attracting highly educated international talent isn’t optional—it’s essential. Professionals who earned their undergraduate degrees at Asian universities now make up a significant share of the STEM workforce in leading metros.

In San Jose, nearly one in five college-educated adults—and over one in three tech workers—earned their first degree in Asia. These workers tend to be also highly credentialed, generally graduating from top-ranked institutions. Similar patterns appear in Seattle and San Francisco, where global talent pipelines have become core to regional competitiveness.

Other regions are falling behind. In places like Miami and across much of the South the share of Asia-educated STEM workers is lower, and the average ranking of their alma maters lags well behind the coasts. Texas metros like Austin and Dallas perform somewhat better on volume, but still trail in quality.

The Midwest follows a similar pattern. While Illinois edges above the national average, most of the region struggles to attract Asia-educated STEM talent at scale—and from top institutions.

In several states, policymakers are pairing global talent pipelines with local inclusion strategies. Recent actions include formally recognizing Lunar New Year, Diwali, and other Asian cultural holidays and hosting public celebrations; directing grant funding to AAPI community-based nonprofits; enacting stronger anti-Asian-hate statutes and reporting systems; appointing Asian Americans to cabinet-level or agency leadership roles; and expanding state scholarships, trade missions, and university partnerships with Asia.

These measures both signal welcome and help sustain the qualified talent described throughout this report. They are also likely to further exacerbate the sorting of Asians in certain metros and states. This uneven distribution reflects—and reinforces—wider disparities in innovation capacity. Regions that build deeper ties to global talent networks will extend their lead. Those that don’t may find it harder to compete in the economy of the future.

The Case of the Vanishing Teller: How Banking’s Entry Level Jobs Are Transforming

By Katherine Townsend Kiernan

The financial services industry is undergoing a seismic transformation. Traditional roles, particularly entry-level positions like bank tellers, are being replaced by hybrid roles that demand advanced digital literacy, complex problem-solving, and sophisticated interpersonal skills. This transformation has troubling implications for the workforce, especially for workers without college degrees, who have historically been concentrated in roles most vulnerable to automation. But with challenge comes opportunity, especially for workers who can develop the right blend of technical and interpersonal skills. Through targeted training programs, policy interventions, and cross-sector partnerships that focus on developing skills, we can create pathways for upward mobility in a dynamic and unpredictable labor market environment.

Who Gets Left Behind: The Vanishing World of Bank Tellers

The role of the bank teller has been quietly fading through a slow shift driven by digital banking, mobile apps, and automation—reshaping which human skills are valued and where opportunity lies. While more than 340,000 teller positions still exist, employment in the role has declined nearly 30% since 2010, and job postings have dropped by almost two-thirds. Tellers today also struggle to climb the career ladder: only 4% transition into higher-paying roles like loan officers. As this entry-level gateway disappears, so do the career pathways that have long supported workers without a four-year degree.

Figure 1. Job Postings for Teller Positions

Source: BGI Analysis of Lightcast Job Postings, 2010-2024

Customers now increasingly demand "human-less" banking experiences for routine transactions, pushing financial institutions to radically redesign customer interactions. In response, two new roles—Relationship Bankers and Universal Bankers—have emerged. These positions reflect a nuanced reality: while human-to-human interaction remains essential, the nature of that interaction has transformed. As their name suggests, these roles are more involved than the original teller role that they are in many ways replacing. Universal and Relationship bankers are expected to know more about lending measures and be able to sell banking products to customers in a way that tellers were generally not expected to do.

No longer focused on cash handling, these roles demand sophisticated skills in digital navigation, product understanding, and interpersonal engagement—bearing little resemblance to the transactional work typical just a decade ago. Yet even these emerging roles reflect the harsh economic realities facing early-career workers in financial services. When these roles first emerged in the early 2010s, they commanded nearly $70,000 annually. Today, median wages are around $52,000–a decline of around one-quarter.

Figure 2. Evolution of Teller Skills - Traditional vs. Emerging Roles

Source: BGI Analysis of Lightcast Job Postings Data 2010 - 2024

Career Mobility and Barriers to Advancement

In 2023, financial services employed over 7 million workers across roughly 23 occupations focused on finance, with 10 of those occupations accessible without a four-year degree. These 10 roles employed 3 million workers—about 43% of the industry's total workforce—with an average salary of $49,513. Accounting for nearly 5% of total financial services industry employment, the teller role seemed a good entry point for workers without degrees to launch a career in financial services. The numbers back this up: 64% of tellers are promoted within three years, according to Burning Glass Institute analysis.

Clicking a level deeper, a more nuanced picture emerges. Many promotions are often semi-lateral moves within the teller occupation (e.g., Teller to Senior Teller). And while the most lucrative transitions are to Personal or Relationship Banker, earning a wage premium of up to $18,000, most only lead to increases of about $6,750 annually, bumping workers to annual salaries of $32,500. If tellers were able to bridge the gap between their current occupation to some of the higher paying non-BA finance roles, their salary potential would double: Tellers who get promoted into a new occupation see new salaries of roughly $68,000 on average. These roles include Loan Officers, Auditors, Financial Specialists, and New Account Clerks.

A look at the data for those advancing to higher-paying occupations highlights educational attainment as a major barrier to mobility for tellers, 83% of whom do not have a bachelor's degree. Of the eight most common roles tellers transition into, most usually require a degree. While some occupations—like Financial Specialists and Sales Representatives—have a more balanced distribution of workers with and without bachelor's degrees, the pattern is clear: roles requiring higher education offer substantially higher wages. The two transitions that do not require additional formal education pay dramatically less than those demanding a college degree. This suggests that salary progression in financial services is systematically constrained by educational requirements.

Figure 3. Pathways in Finance Limited by Education Barriers

Source: BGI Analysis of Worker Career Histories; National OEWS; Lightcast Job Postings (2023)

The Fintech Revolution: A Mirage of Opportunity

The rapid growth of financial technology has been consistently portrayed as a democratizing force—a sector promising unprecedented career mobility for workers without traditional four-year degrees. This narrative suggests that coding bootcamps, online learning platforms, and technical certifications could rapidly transform entry-level workers into high-earning tech professionals.

But despite the industry's reputation for disruption, 76% of FinTech workers hold bachelor's degrees, and the sector remains dramatically smaller than traditional banking. Indeed, while about 1 in every 4 workers in FinTech (not including customer service/call center reps) do not have a BA, all the occupations in the sector typically require one. In corporate banking roles, most of the occupations typically require a degree, but roughly 1 in 3 people do not have a degree, indicating a greater opportunity for skills-based transitions in this area of banking. Corporate banking is seven times larger than FinTech, while branch banking is eight times its size. Moreover, employers remain skeptical of non-traditional training, frequently defaulting to degree requirements as a proxy for skill verification. The result is a sector that promises radical opportunity but predominantly reproduces existing educational and professional gatekeeping mechanisms.

Figure 4. Sub-BA employment by sub-sector

Skills as Workforce Adaptation Strategy

The challenges facing bank tellers are not an isolated phenomenon. As digital innovations systematically redesign traditional roles, the skills required for career success are fundamentally changing. The teller's journey—from a transactional, cash-handling position to a more complex role demanding digital literacy and sophisticated interpersonal capabilities—serves as a critical case study in workforce adaptation.

This evolution reveals a pivotal insight: success in the modern financial services landscape no longer depends on performing routine tasks, but on developing a dynamic, integrated skill set that can navigate rapid technological change. Emerging positions are increasingly centered around communications and sales practices—skills that develop through experience and don't necessarily require structured educational or technical training. Nevertheless, some technical skills remain highly valued: skills in mobile banking and data analytics have a growing importance within the financial sector, offering professionals a 37% wage premium. But the most promising career trajectories emerge at the intersection of technical skills and sophisticated interpersonal capabilities.

Figure 5. Key Skill Characteristics

Source: BGI Analysis of Lightcast Job Postings

Spotlight on Hispanic Workers in Financial Services

The technological transformation of financial services intersects critically with workforce demographics, presenting both challenges and opportunities for Hispanic professionals. Currently representing 17.3% of the financial services workforce—slightly below their 19% share of the overall US workforce—Hispanic workers are disproportionately concentrated in roles most vulnerable to technological displacement.

Hispanic workers are overrepresented in positions like tellers, which are rapidly declining due to automation and digital banking trends, while simultaneously being underrepresented in higher-paying roles like loan officers. The representation numbers are revealing: tellers are 21% Hispanic (rising to 28% at five top retail banks), while loan officers are just 13% Hispanic (15% at top 5 banks).

Wage data further underscores these economic barriers. Most finance occupations earn between $50,000 and $75,000 annually, but higher-earning banking positions show significantly lower representation of Hispanic workers. For Hispanic professionals, particularly those historically concentrated in entry-level banking roles, emerging skill-based pathways represent more than career transitions—they offer a strategic approach to economic advancement, circumventing traditional educational barriers and creating more resilient professional identities.

Figure 6. Major Finance Occupations by Annual Salary and Share Hispanic

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Current Population Survey, Household Data, Annual Averages, Table 11: Employed Persons by Detailed Occupation, Sex, Race, and Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. National Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS). U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.bls.gov/oes/tables.htm.

Looking Ahead

As technological advancements continue to reshape industries, the transformation of roles like bank tellers serves as a powerful example of how workforce adaptation is crucial for economic survival. Economic survival now depends on viewing skills as portable assets rather than sector-specific credentials. In an era of technological disruption, skills must become the primary currency of career advancement, particularly for workers without traditional educational credentials. The skills gap—while a significant challenge—also represents an opportunity: by focusing on upskilling and reskilling, we can unlock new pathways for workers, particularly those without traditional college degrees, to advance in their careers.

Workers must become adept at translating their capabilities across multiple professional domains, with workforce development systems providing the critical infrastructure to support these transformations.

To realize this potential, workforce development systems must evolve. Employers, policymakers, and educators must collaborate to build an infrastructure that fosters continuous learning, identifies emerging skill needs, and creates pathways for career progression that are flexible and accessible. Targeted training, strategic policy interventions, and cross-sector partnerships are critical to bridging the gap and ensuring that workers are equipped to thrive in a technology-driven economy.

As we look toward the future, the success of this transformation will be determined by our ability to adapt not just to technological change, but to the evolving needs of the workforce. By prioritizing skills development, we can create a more resilient, equitable labor market that empowers workers to transition seamlessly between industries and roles, ensuring long-term economic mobility and growth.

How Changing College Majors Are Reshaping the Future Workforce

Today’s students are making strategic choices that align with a fast-changing labor market — but sharp declines in fields like education, social work, and the humanities raise red flags for our society’s future. This deep dive explores what shifting college major trends reveal about economic opportunity, societal priorities, and the risks ahead.

By Gad Levanon and Tomer Stern

The college majors that undergraduates have declared in recent years are a leading indicator of where tomorrow’s talent will flow. When those preferences shift, the effect ripples through graduate-school pipelines, corporate recruiting, and ultimately the occupational structure of the economy. To isolate that effect, we ran a controlled thought-experiment: if the only change that occurred between 2018 and 2023 was in students’ majors, how would the mix of occupations shift?

Using American Community Survey micro-data, we compared the major distribution of recent graduates in 2018 and 2023 and applied a fixed 2023 major-to-occupation cross-walk—built from employed 30- to 32-year-olds—to each cohort. Everything else (demographic composition, population size) was held constant. The result is two hypothetical workforces: one reflecting the 2018 major mix and one reflecting 2023. The gap between them pinpoints where talent pipelines are expanding or shrinking solely due to student choice.

One key theme emerges: students are pivoting into majors aligned to high paying careers. Many are flooding into technology, engineering, and advanced health sciences, even as they retreat from less lucrative majors like education, social work, and journalism – as well as the humanities more broadly. On some level, this reflects understandable concerns about employability in an increasingly precarious job market for new grads and ever-rising tuition costs. At the same time, some of the majors in decline portend future shortages in teaching, caregiving, and civic leadership, and may weaken society’s ability to navigate human challenges in an AI-driven world.

These changes will have significant implications for the supply of workers by occupation. Here are some notable examples:

The surge in computer-science enrollment—up 52 percent since 2018—translates into roughly one-fifth more software developers and cybersecurity analysts in the coming pipeline.

Engineering talent is broadening, not just deepening. Double-digit increases in biomedical, aerospace, industrial and mechanical majors signal a robust stream of skills for advanced-manufacturing, climate-tech and space-systems roles.

Health-care projections are mixed. For example, while nurse-anesthetist and nurse-practitioner supply is set to expand by 15–22 percent, the ranks of occupational and physical therapists are on course to fall about 10 percent.

Teacher preparation is moving the wrong way. A continued slide in education and humanities majors implies a 7–9 percent drop in new K-12 and special-education teachers, tightening shortages that districts already struggle to fill.

Humanities and journalism decline thin the creative pipeline: future editors, writers and reporters could shrink by up to one-fifth.

Finally, social-service talent contracts, pointing to a 4 percent dip in child- and family-social-worker supply—small in percentage terms, but critical given the shortages in these occupations.

The Rise of Tech and Health Majors

To quantify the change in major preferences, using American Community Survey micro-data, we compared the major distribution of college graduates aged 22-24 in 2018 and 2023, and computed the percent change in the share of each major.

Two groups of college majors have seen especially large increases in popularity over the past five years: technology and health-related fields. These shifts reflect how today’s students are responding to some of the most powerful forces shaping the U.S. economy and society — from the rise of artificial intelligence and data science to the aging of the population and the lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Technology majors, particularly computer and information sciences, have surged. This category saw the largest increase in share among all major groups, growing by 42% from 2018 to 2023. Within that, computer science alone rose by an impressive 52%, underscoring the economy-wide shift toward digital skills and the growing appeal of careers in tech, data, and AI. Engineering also saw a notable uptick, driven by demand for applied technical skills across industries.

Health-related majors expanded significantly as well. Nursing grew by 32%, public health by 29%, and biomedical engineering by a striking 48%. General medical and health services majors increased by 19%. These trends reflect not only the shock of the pandemic but also long-standing demographic shifts — particularly the aging of the baby boomer generation and the growing demand for health care services.

Some of the most dramatic growth occurred in biology and mental health–adjacent fields. Neuroscience majors nearly doubled (+85%), while microbiology (+69%) and biochemical sciences (+63%) also saw exceptional gains. These increases likely stem from a mix of heightened awareness of infectious diseases, rising concern over mental health, and rapid advances in biomedical research and innovation. For many students, these majors represent a blend of cutting-edge science and meaningful societal impact.

Together, these shifts show how student interests are increasingly aligned with future-facing sectors of the economy — and how the classroom is already adapting to a changing world.

The Decline of Humanities, Pure Sciences, and Service Fields

While technology and health majors have surged, other areas of study have seen sharp declines — especially in the liberal arts, some hard sciences, and traditional service professions.

Liberal arts and humanities majors have experienced some of the most significant drops. From 2018 to 2023, the number of students majoring in liberal arts and humanities fell by nearly 30 percent. Area, ethnic, and civilization studies declined by 39 percent, while English language and literature dropped by 15 percent and foreign languages by 16 percent. These fields, once considered the intellectual foundation of a college education, are increasingly seen as disconnected from clear career outcomes.

The decline in humanities enrollment reflects more than changing student preferences—it raises questions about the future role of these disciplines. Fields like history, literature, and philosophy have long developed critical thinking, ethical reasoning, and cultural understanding—skills that contribute to both personal growth and democratic life. As artificial intelligence automates more technical tasks, human skills like creativity, empathy, and judgment may become more valuable, not less. These are often cultivated through the humanities. While the shift toward career-focused education is understandable, maintaining space for the humanities could help ensure society remains thoughtful, adaptable, and equipped to meet the challenges of an AI-driven world.

The hard sciences have not been immune to this trend. Majors in chemistry and mathematics declined by 19 percent and 26 percent, respectively. Although these fields are part of the broader STEM category, they are more academically oriented and less directly tied to the booming tech and health sectors that dominate today’s labor market. Many students may be opting instead for applied disciplines like computer science, data science, or biomedical engineering, which offer more immediate and lucrative job prospects.

The Decline of Education Majors

Majors in education are also on the decline. Education administration and teaching saw an 8.8 percent drop during this period — a relatively modest decline compared to other fields, but still notable given the critical need for educators across the country. The projected decline in teacher supply is partly driven by a decrease in women choosing education-related majors. This trend coincides with a shift towards greater gender parity in traditionally male-dominated fields like management, finance and computer science.

The projected decrease in the population aged 5-19 could lead to slower growth in teacher employment, potentially discouraging students from pursuing teaching careers. In addition, teaching is not attractive to workers who want to work from home.

Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic brought intense pressures on teachers, including burnout, political scrutiny, and staffing shortages. These factors may have made the profession less appealing, even to students motivated by a desire to make a difference.